Chinese Copper Vase With 6 on the Bottom Copper Shell and Art Work

Chinese Ming Dynasty cloisonné enamel basin, using nine colours of enamel

Cloisonné (French pronunciation: [klwazɔne]) is an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with colored material held in identify or separated by metallic strips or wire, normally of golden. In recent centuries, vitreous enamel has been used, but inlays of cut gemstones, drinking glass and other materials were also used during older periods; indeed cloisonné enamel very probably began every bit an easier fake of cloisonné work using gems. The resulting objects tin too be called cloisonné.[1] The ornament is formed past kickoff adding compartments (cloisons in French[ii]) to the metal object by soldering or affixing silverish or gold equally wires or thin strips placed on their edges. These remain visible in the finished piece, separating the different compartments of the enamel or inlays, which are often of several colors. Cloisonné enamel objects are worked on with enamel powder made into a paste, which then needs to be fired in a kiln. If gemstones or colored glass are used, the pieces need to be cutting or ground into the shape of each cloison.

In artifact, the cloisonné technique was generally used for jewellery and pocket-size fittings for clothes, weapons or similar small objects decorated with geometric or schematic designs, with thick cloison walls. In the Byzantine Empire techniques using thinner wires were developed to allow more pictorial images to be produced, mostly used for religious images and jewellery, and by so always using enamel. This was used in Europe, specially in Carolingian and Ottonian art. By the 14th century this enamel technique had been replaced in Europe by champlevé, but had then spread to Mainland china, where it was presently used for much larger vessels such as bowls and vases; the technique remains mutual in China to the present day, and cloisonné enamel objects using Chinese-derived styles were produced in the W from the 18th century.

In Middle Byzantine compages "cloisonné masonry" refers to walls built with a regular mix of stone and brick, often with more of the latter. The 11th or 12th-century Pammakaristos Church in Istanbul is an case.[3]

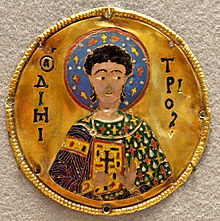

Byzantine cloisonné enamel plaque of St Demetrios, c. 1100, using the senkschmelz or "sunk" technique and the new thin-wire technique

History [edit]

Ancient world [edit]

Cloisonné starting time developed in the jewellery of the ancient About East, and the earliest enamel all used the cloisonné technique, placing the enamel within small cells with gold walls. This had been used equally a technique to concur pieces of stone and gems tightly in place since the tertiary millennium BC, for instance in Mesopotamia, and so Egypt. Enamel seems probable to have developed as a cheaper method of achieving similar results.[4]

The earliest undisputed objects known to apply enamel are a group of Mycenaean rings from Graves in Republic of cyprus, dated to the 12th century BC, and using very thin wire.[five]

In the jewellery of ancient Egypt, including the pectoral jewels of the pharaohs, thicker strips form the cloisons, which remain small-scale.[half-dozen] In Egypt gemstones and enamel-like materials sometimes chosen "glass-paste" were both used.[7] Although Egyptian pieces, including jewellery from the Tomb of Tutankhamun of c. 1325 BC, are oft described equally using "enamel", many scholars dubiousness the glass paste was sufficiently melted to be properly so described, and employ terms such equally "glass-paste". It seems possible that in Egyptian conditions the melting point of the glass and gold were too shut to make enamel a viable technique. However, there appear to exist a few bodily examples of enamel, perhaps from the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt (kickoff 1070 BC) on.[viii] Simply it remained rare in both Arab republic of egypt and Hellenic republic.

The technique appears in the Kuban during the Scythian period, and was perhaps carried by the Sarmatians to the ancient Celts, but they essentially used the champlevé technique.[9] Later, enamel was only ane of the fillings used for the modest, thick-walled cloisons of the Late Antiquarian and Migration Menses fashion. At Sutton Hoo, the Anglo-Saxon pieces mostly use garnet cloisonné, but this is sometimes combined with enamel in the aforementioned slice. A trouble that adds to the doubt over early enamel is artefacts (typically excavated) that appear to take been prepared for enamel, but have now lost whatever filled the cloisons.[x] This occurs in several different regions, from ancient Egypt to Anglo-Saxon England. One time enamel becomes more common, as in medieval Europe after almost 1000, the supposition that enamel was originally used becomes safer.

Byzantium and Europe [edit]

The Byzantines perfected a unique course of cloisonné icons. Byzantine enamel spread to surrounding cultures and a particular type, often known as garnet cloisonné is widely found in the Migration Flow fine art of the "barbaric" peoples of Europe, who used gemstones, especially ruby garnets, as well as glass and enamel, with small thick-walled cloisons. Red garnets and gold made an attractive contrast of colours, and for Christians the garnet was a symbol of Christ. This type is now thought to have originated in the Late Antiquarian Eastern Roman Empire and to have initially reached the Migration peoples as diplomatic gifts of objects probably made in Constantinople, and then copied by their ain goldsmiths.[xi] Glass-paste cloisonné was made in the aforementioned periods with similar results – compare the golden Anglo-Saxon fitting with garnets (right) and the Visigothic brooch with glass-paste in the gallery.[12] Thick ribbons of gold were soldered to the base of the sunken area to be decorated to make the compartments, before adding the stones or paste.[13] [fourteen] In the Byzantine world the technique was adult into the thin-wire style suitable only for enamel described below, which was imitated in Europe from nearly the Carolingian period onwards.

The dazzling technique of the Anglo-Saxon clothes fittings from Sutton Hoo include much garnet cloisonné, some using remarkably sparse slices, enabling the patterned gold below to be seen. There is too imported millifiori glass cut to fit similar the gems. Sometimes compartments filled with the different materials of cut stones or glass and enamel are mixed to ornament the same object, as in the Sutton Hoo purse-lid.[xv]

From about the 8th century, Byzantine art began again to utilise much thinner wire more freely to permit much more circuitous designs to be used, with larger and less geometric compartments, which was only possible using enamel.[16] These were still on relatively small objects, although numbers of plaques could be prepare into larger objects, such as the Pala d'Oro, the altarpiece in Saint Marker's Cathedral, Venice. Some objects combined thick and thin cloisons for varied result.[17] The designs often (as at right) contained a generous background of obviously gilt, as in gimmicky Byzantine mosaics. The area to be enamelled was stamped to create the main depression, pricked to help the enamel adhere, and the cloisons added.[18]

Two different techniques in Byzantine and European cloisonné enamel are distinguished, for which the German names are nevertheless typically used in English language. The earliest is the Vollschmelz ("full" enamel, literally "full melt") technique where the whole of a gold base plate is to exist covered in enamel. The edges of the plate are turned up to course a reservoir, and gilt wires are soldered in place to form the cloisons. The enamel pattern therefore covers the whole plate. In the Senkschmelz ("sunk" enamel, literally "sunk melt") technique the parts of the base plate to hold the design are hammered downwardly, leaving a surrounding gilded background, as also seen in contemporary Byzantine icons and mosaics with gold glass backgrounds, and the saint illustrated hither. The wires and enamels are then added every bit before. The outline of the blueprint will be apparent on the opposite of the base plate.[nineteen] The transition between the ii techniques occurs around 900 in Byzantine enamel,[20] and 1000 in the West, though with of import earlier examples.[21]

The plaques with apostles of around the latter date on the Holy Crown of Hungary show a unique transitional phase, where the base plaque has hammered recesses for the design, as in senkschmelz piece of work, but the enamel covers the whole plaque except for thick outlines effectually the figures and inscriptions, as in the vollschmelz technique (meet the gallery below for examples of this technique and vollschmelz work).[22] Some 10th-century pieces achieve a senkschmelz effect by using two plates superimposed on each other, the upper 1 with the design outline cut out and the lower ane left plain.[23]

In medieval Western Europe cloisonné enamel technique was gradually overtaken past the rise of champlevé enamel, where the spaces for the enamel to fill are created by making recesses (using various methods) into the base of operations object, rather than building up compartments from it, equally in cloisonné. This happened during the 11th century in almost centres in Western Europe, though not in Byzantium; the Stavelot Triptych, Mosan art of around 1156, contains both types, but the inner cloisonné sections were probably gifts from Constantinople. Champlevé immune increased expressiveness, specially in human fugures, and was also cheaper, equally the metal base was usually but copper and if gold was used, it was mostly to club surrounding blank metal. In plough champlevé was replaced by the 14th or 15th century past painted enamels, in one case techniques were evolved that allowed the enamel to exist painted onto a flat background without running. Limoges enamel was a keen centre for both types.[24]

Plique-à-jour is a related enameling technique which uses clear enamels and no metal backplate, producing an object that has the advent of a miniature stained drinking glass object - in effect cloisonné with no backing. Plique-a'-jour is commonly created on a base of operations of mica or thin copper which is after peeled off (mica) or etched away with acid (copper).[25] In the Renaissance the extravagant style of pieces effectively of plique-à-jour backed onto glass or rock crystal was developed, just was never very mutual.[26]

Other ways of using the technique have been developed, just are of minor importance. In 19th century Nihon it was used on pottery vessels with ceramic glazes, and information technology has been used with lacquer and modern acrylic fillings for the cloisons.[27] A version of cloisonné technique is often used for lapel badges, logo badges for many objects such as cars, including BMW models, and other applications, though in these the metal base of operations is unremarkably cast with the compartments in place, so the apply of the term cloisonné, though common, is questionable. That technique is correctly referred to by goldsmiths, metalsmiths and enamellists as champlevé.

-

Visigothic 6th-century hawkeye-fibula, from Spain with garnets, amethysts, and colored glass, and some cloisons at present empty.

Cathay [edit]

An 18th-century Chinese wine pot with cloisonné enamel and gold bronze; the blueprint was loosely based on Zhou Dynasty inlaid bronzes of the 5th–4th centuries BC

From Byzantium or the Islamic world the technique reached China in the thirteen–14th centuries; the first written reference is in a book of 1388, where information technology is called "Dashi ware". No Chinese pieces clearly from the 14th century are known, the earliest datable pieces being from the reign of the Xuande Emperor (1425–35), which however show a full use of Chinese styles suggesting considerable experience in the technique.[28] It was initially regarded with suspicion by Chinese connoisseurs, firstly as beingness foreign, and secondly as appealing to feminine taste. However, past the beginning of the 18th century the Kangxi Emperor had a cloisonné workshop among the many Imperial factories. The near elaborate and highly valued Chinese pieces are from the early Ming Dynasty, especially the reigns of the Xuande Emperor and Jingtai Emperor (1450–57), although 19th century or modern pieces are far more common. The Chinese industry seems to have benefited from a number of skilled Byzantine refugees fleeing the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, although based on the name alone, it is far more likely China obtained knowledge of the technique from the middle east. In much Chinese cloisonné blue is usually the predominant colour, and the Chinese proper name for the technique, jingtailan ("Jingtai blue ware"), refers to this, and the Jingtai Emperor. Quality began to decline in the 19th century. Initially heavy bronze or brass bodies were used, and the wires soldered, but later on much lighter copper vessels were used, and the wire glued on before firing.[29] [30] The enamels compositions and the pigments alter with fourth dimension.

Chinese cloisonné is sometimes confused with County enamel, a type of painted enamel on copper that is more closely related to overglaze enamels on Chinese porcelain, or enamelled glass. This is painted on freehand so does not apply partitions to hold the colours separate.[31]

In Byzantine pieces, and fifty-fifty more in Chinese work, the wire by no means ever encloses a split color of enamel. Sometime a wire is used just for decorative effect, stopping in the centre of a field of enamel, and sometimes the boundary between two enamel colors is not marked past a wire. In the Byzantine plaque at right the offset characteristic may be seen in the top wire on the saint'due south black sleeve, and the second in the white of his eyes and collar. Both are also seen in the Chinese bowl illustrated at top right.

-

Chinese shrine for a Bodhisattva, 1736–1795. Shrine: Cloisonné enamel on copper blend; Effigy is copper with gems

-

Chinese cloisonné enamel incense burner, 17th-18th centuries

-

Chinese enameled and gilt candlestick from the 18th or 19th century, Qing dynasty

Japan [edit]

Owari Cloisonne Enamel Octagon by Takemasa Tamura[32]

The Japanese too produced large quantities from the mid-19th century, of very high technical quality.[33] During the Meiji era, Japanese cloisonné enamel reached a technical peak, producing items more than advanced than whatever that had existed before.[34] The period from 1890 to 1910 was known as the "Golden age" of Japanese enamels.[35] An early on heart of cloisonné was Nagoya during the Owari Domain, with the Ando Cloisonné Visitor the leading producer. Later centres were Kyoto and Edo, and Kyoto resident Namikawa Yasuyuki and Tokyo (renamed from Edo) resident Namikawa Sōsuke exhibited their works at World'southward fair and won many awards.[36] [37] [38] In Kyoto Namikawa became one of the leading companies of Japanese cloisonné. The Namikawa Yasuyuki Cloisonné Museum is specifically defended to information technology. In Nihon cloisonné enamels are known as shippō-yaki (七宝焼). Japanese enamels were regarded as incomparable thanks to the new achievements in design and colouring.[39]

-

Matching Pair of Cloisonné Vases, c. 1800–1894, from the Oxford College Athenaeum of Emory University

-

Tokyo Cloisonne Enamel, Shōtai Shippō past Namikawa Sōsuke (c. 1900), translucent plique-a-jour enamel on silverish.

-

Pair of 2-fold Screens 1900–1905, Nagoya, Japan

-

Russian federation [edit]

The first Russian cloisonné adult from Byzantine models during the flow of Kievan Rus, and has mainly survived in religious pieces. Kiev was mayhap the only centre.[xl] The industry stopped with the Mongol invasion of Russia merely revived in Novgorod past the end of the 14th century, at present using champlevé.[41] Cloisonné barely returned until the 19th century, when it was used in revivalist styles by the Business firm of Fabergé and Khlebnikov. Fabergé developed a style of raised and contoured metal shapes rising from the base plate, which were filled, though more thinly than in most cloisonné (effectively painted), leaving the metallic edges articulate. This is usually called cloisonné or "raised cloisonné", though the appropriateness of the term might exist disputed,[42] equally in other types of cloisonné the surface is smooth, which is not the case with these.

Modern process [edit]

Calculation cloisons according to the pattern previously transferred to the workpiece

Calculation frit with dropper after sintering cloisons. Upon completion the piece volition exist fired, then ground (repeating as necessary) then polished and electroplated

Get-go the object to be busy is made or obtained; this will ordinarily be made by different craftspeople. The metal usually used for making the body is copper, since information technology is inexpensive, light and hands hammered and stretched, simply gold, silver or other metals may be used. Cloisonné wire is made from fine silver or fine gold and is usually about .010 x .040 inches in cross section. It is bent into shapes that define the colored areas. The bends are all done at correct angles, so that the wire does not curve up. This is washed with small pliers, tweezers, and custom-made jigs. The cloisonné wire pattern may consist of several intricately constructed wire patterns that fit together into a larger blueprint. Solder can be used to bring together the wires, but this causes the enamel to discolour and form bubbles afterward on. Most existing Byzantine enamels have soldered cloisons, nevertheless the use of solder to adhere the cloison wires has fallen out of favor due to its difficulty, with the exception of some "purist gimmicky enamellists" who create fine sentinel faces and high quality very expensive jewelry. Instead of soldering the cloisons to the base of operations metal, the base of operations metal is fired with a sparse layer of clear enamel. The cloisonné wire is glued to the enamel surface with gum tragacanth. When the gum has dried, the piece is fired once more to fuse the cloisonné wire to the articulate enamel. The gum burns off, leaving no rest.

Vitreous enamels in the unlike colors are ground to fine powders in an agate or porcelain mortar and pestle, so done to remove the impurities that would discolor the fired enamel.[43] The enamel is made from silica, niter, and pb oxide to which metallic oxides are added for coloring. These ingredients are melted together, forming a glassy frit which is basis over again before application. Each color of enamel is prepared this fashion earlier information technology is used and then mixed with a very dilute solution of gum tragacanth. Using fine spatulas, brushes or droppers, the enameler places the fine colored pulverisation into each cloison. The piece is left to dry completely before firing, which is done past putting the article, with its enamel fillings, in a kiln. The enamel in the cloisons will sink down a lot after firing, due to melting and shrinkage of the granular nature of the glass powder, much as sugar melting in an oven. This procedure is repeated until all cloisons are filled to the top of the wire border.

3 styles of cloisonné are most frequently seen: concave, convex, and apartment. The finishing method determines this terminal appearance.[44] With concave cloisonné the cloisons are non completely filled. Capillary action causes the enamel surface to bend upward against the cloisonné wire when the enamel is molten, producing a concave appearance. Convex cloissoné is produced by overfilling each cloison, at the last firing. This gives each colour surface area the advent of slightly rounded mounds. Flat cloisonné is the most common. After all the cloisons are filled the enamel is ground downwardly to a shine surface with lapidary equipment, using the same techniques every bit are used for polishing cabochon stones. The top of the cloisonné wire is polished so it is flush with the enamel and has a bright lustre.[45] [46] Some cloisonné wire is electroplated with a thin film of gold, which will not tarnish every bit argent does.[47] [48]

Examples [edit]

Enamel [edit]

- The 8th-century Irish Ardagh Beaker

- The Alfred Jewel, a 9th-century Anglo-Saxon ornament

- The Khakhuli triptych, a big golden altarpiece with over 100 Georgian and Byzantine plaques, dating from the eighth to 12th centuries, said to be the largest enamelled work of fine art in the globe.

- the eyes of the tenth century Golden Madonna of Essen

- The 12th century Mosan Stavelot Triptych, combining cloisonné and champlevé work.

- The Khalili Imperial Garniture from tardily 19th century Nihon

Gems and glass [edit]

- The Pectoral of Tutankhamun, (image), and several others.

- The 5th century grave goods of Childeric I, last heathen king of the Franks, died c. 481

- The 5th-century Germanic Treasure of Pouan

- The 6th-century Merovingian Treasure of Gourdon

Collections [edit]

Collections of Japanese cloisonné enamels are held at major museums including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Namikawa Yasuyuki Cloisonné Museum in Kyoto is dedicated to the technique. A collection of 150 Chinese cloisonné pieces is at the G.West. Vincent Smith Art Museum in Springfield, Massachusetts.[ citation needed ] The Khalili Drove of Japanese Meiji Art includes 107 cloisonné enamel art works, including many works by Namikawa Yasuyuki, Namikawa Sosuke, and Ando Jubei.[49] Researchers take used the collection to constitute a chronology of the development of Japanese enamelling.[50]

Gallery [edit]

-

Mod cloisonné enamel beads

-

Cloisonné artwork of Korea (namjung cloisonné)

-

Detail showing design and partially completed cloisons

Run across too [edit]

- Champlevé, enamelling into hollows made in a metallic surface

- Polychrome vitreous enamel, where the drinking glass is melted onto the object, is too washed without separating wires.

- Yūzen , a like technique for dying cloth, with pools of dye between ridges of temporary resist paste

Notes [edit]

- ^ Osborne, 331

- ^ In French "cloison" is a general word for "compartment" or "partition" or "cell", in English the word is usually simply used in the specialized context of cloisonné work, and apparently dentistry (OED, "Cloison")

- ^ Darling, Janina Yard., Compages of Hellenic republic, p. xliii, 2004, Greenwood Press, ISBN 9780313321528, google books, a rather more restricted definition than some sources employ.

- ^ Osborne, 331

- ^ Osborne, 331; Michaelides, Panicos, The Earliest Cloisonne Enamels from Republic of cyprus, article from Glass on Metal, the Enamellist'southward Magazine, April 1989, online Archived 2009-04-12 at the Wayback Machine. See also Wilson, Nigel, ed. (2006). "Enamel". Encyclopedia of Aboriginal Hellenic republic. Psychology Press. p. 259. ISBN978-0-415-97334-two.

- ^ Clark, 67-68. For an case meet Pectoral and Necklace of Sithathoryunet Metropolitan Museum

- ^ Egyptian Paste article from Ceramics Today. Encounter likewise Egyptian faience. In that location are disputes every bit to whether, or when, such materials were fired with the object, or fired separately start and then cutting into pieces to be inlaid similar gems. It seems both methods may have been used. See Twenty-four hours, Lewis Foreman, Enamelling: A Comparative Account of the Evolution and Practise of the Fine art, 7-10, 1907, Batsford

- ^ Ogden, 166

- ^ Osborne, 331

- ^ Osborne, 331

- ^ Belatedly Artifact, 464. Run into here for scientific materials analysis

- ^ Harden, Donald Benjamin (1956). Dark-age U.k.: Studies Presented to E. T. Leeds. Methuen – via Google Books.

- ^ Youngs, 173

- ^ Green, 87-88

- ^ Ness, 110-114; Purse chapeau from the ship-burial at Sutton Hoo British Museum Google Arts & Civilization app. Retrieved two April 2019.

- ^ The date of the change is uncertain, partly because Early Byzantine enamels were much forged in 19th century Russia, rather confusing historians.

- ^ Ross, 217

- ^ Ross, 99, describing what appear to be trainee pieces in bronze, never completed.

- ^ Bàràny-Oberschall, 122-123; Lasko, 8—he prefers ""full" enamel" and ""sunk" enamel"; British Museum on using the German names

- ^ Campbell, 11

- ^ Earlier Western examples are few merely include the cover of the Lindau Gospels, the foot-reliquary of St Andrew fabricated for Egbert of Trier, and the Majestic Crown of the Holy Roman Empire; Lasko, 84-85

- ^ Bàràny-Oberschall, 122-123

- ^ Campbell, 13 effigy 7

- ^ Osborne, 332-334

- ^ Campbell, 38-40

- ^ Cleveland mirror-back (illustrated)

- ^ Carpenter

- ^ Sullivan, 239; Dillon, 58-59.

- ^ Dillon, 58-59

- ^ Eckens, Marie (September 1982). "The True Fine art of Cloisonne". Antiques. Orange Coast Magazine. p. 96.

This was improved further in the second of the 17th Century when copper--a more pliable metallic--replaced bronze as the metal for both bases and cloisons.

- ^ Osborne, 201-202; Nillson, Jan-Brik, "Canton enamel", Gotheburg.com

- ^ "TAMURA SHIPPO". TAMURA SHIPPO . Retrieved 2022-03-16 .

- ^ V&A

- ^ Earle, 252

- ^ Irvine, Gregory (2013). "Wakon Yosai- Japanese spirit, Western techniques: Meiji period arts for the Westward". In Irvine, Gregory (ed.). Japonisme and the rise of the modernistic art movement : the arts of the Meiji menstruum : the Khalili collection. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 177. ISBN978-0-500-23913-ane. OCLC 853452453.

- ^ Yūji Yamashita. 明治の細密工芸 p.122, p.132. Heibonsha, 2014 ISBN 978-4582922172

- ^ Toyoro Hida, Gregory Irvine, Kana Ooki, Tomoko Hana and Yukari Muro. Namikawa Yasuyuki and Japanese Cloisonné The Attraction of Meiji Cloisonné: The Aesthetic of Translucent Blackness, pp.182-188, The Mainichi Newspapers Co, Ltd, 2017

- ^ "Japanese Cloisonné Industry". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-x-03. Retrieved 2015-ten-29 .

- ^ "Japanese Fine art Enamels". The Decorator and Furnisher. 21 (5): 170. 1893. ISSN 2150-6256. JSTOR 25582341.

Nosotros doubtfulness if any course of the enameller'south art can equal the work executed in Japan, which is distinguished by peachy freedom of design, and the well-nigh exquisite gradations of color.

- ^ Osborne, 677

- ^ Osborne, 680

- ^ Example in the Cleveland Museum of Art

- ^ John Blair; Nigel Ramsay (1991). English Medieval Industries: Craftsmen, Techniques, Products. A&C Blackness. pp. 127–. ISBN978-1-85285-326-6.

- ^ Matthews, 146-147

- ^ Felicia Liban; Louise Mitchell (6 July 2012). Cloisonné Enameling and Jewelry Making. Courier Corporation. pp. 92–. ISBN978-0-486-13600-4.

- ^ Glenice Lesley Matthews (1984). Enamels, Enameling, Enamelists . Chilton Volume Visitor. ISBN978-0-8019-7285-0. [ page needed ]

- ^ Stephanie Radok (2012). An Opening: Twelve Honey Stories about Art. Wakefield Press. pp. 104–. ISBN978-1-74305-043-nine.

- ^ Rayner W. Hesse (2007). Jewelrymaking Through History: An Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Grouping. pp. 88–. ISBN978-0-313-33507-5.

- ^ "Meiji No Takara – Treasures of Imperial Japan: Enamel". Khalili Collections . Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Earle, 254

References [edit]

- Bàràny-Oberschall, Magda de, "Localization of the Enamels of the Upper Hemisphere of the Holy Crown of Republic of hungary", The Fine art Bulletin, Vol. 31, No. 2 (Jun., 1949), pp. 121–126, JSTOR 3047226

- Campbell, Marian. An Introduction to Medieval Enamels, 1983, HMSO for 5&A Museum, ISBN 0112903851

- Carpenter, Woodrow, Cloisonné Primer, from Glass on Metal, the Enamellist's Magazine, June 1995, online

- Clark, Grahame, Symbols of Excellence: Precious Materials as Expressions of Status, Cambridge University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-521-30264-i, ISBN 978-0-521-30264-7, Google Books

- Cosgrove, Maynard Giles, The enamels of China and Nihon, champlevé and cloisonné, London, Hale, 1974.

- Dillon, Michael, Communist china: a historical and cultural dictionary, Routledge, 1998, ISBN 0-7007-0439-6, ISBN 978-0-7007-0439-two, Google books

- Earle, Joe (1999). Splendors of Meiji : treasures of imperial Japan : masterpieces from the Khalili Collection. Saint petersburg, FL: Broughton International Inc. ISBN1874780137. OCLC 42476594.

- Gardner's Art Through the Ages, [1]

- Dark-green: Charles Green, Barbara Green, Sutton Hoo: the excavation of a royal ship-burial, 2nd Edition, Seafarer Books, 1988, ISBN 0-85036-241-v, ISBN 978-0-85036-241-i, Google books

- Harden, Donald B., Dark-age Britain, Taylor & Francis, 1956

- Belatedly artifact: a guide to the postclassical globe, various authors, Harvard University Press reference library, Harvard University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-674-51173-5, ISBN 978-0-674-51173-vi,Google books

- Kırmızı Burcu, Colomban Philippe, Béatrice Quette, On-site Analysis of Chinese Cloisonné Enamels from 15th to 19th century, Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 41 (2010) 780–790. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jrs.2516/abstract

- Lasko, Peter, Ars Sacra, 800–1200, Penguin History of Art (at present Yale), 1972 (nb, 1st edn.)

- Ogden, Jack, "Metal", in Ancient Egyptian Materials and Applied science, eds. Paul T. Nicholson, Ian Shaw, 2000, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521452570, 9780521452571, google books

- Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0198661134

- Nees, Lawrence, Early Medieval Art, Oxford History of Art, 2002, Oxford Upward

- Ross, Marvin C., Catalogue of the Byzantine and Early Medieval Antiquities: Jeweelry, Enamels, and fine art of the Migration Menses, Dumbarton Oaks, 2006, ISBN 0-88402-301-Ten, 9780884023012, Google books

- Sullivan, Michael, The arts of Prc, 4th edn, University of California Printing, 1999, ISBN 0-520-21877-nine, ISBN 978-0-520-21877-2, Google books

- Susan Youngs (ed), "The Work of Angels", Masterpieces of Celtic Metalwork, 6th-9th centuries Advertising, 1989, British Museum Press, London, ISBN 0-7141-0554-6

- "Five&A": "Japanese Cloisonné: the Seven Treasures". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-02-23. Retrieved 2009-08-xxx .

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cloisonné. |

- Cloisonné Manufactures and Tutorials at The Ganoksin Projection

- Chinese Cloisonné, Department of Asian Art, in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 2000–2004

- An Interview with Gimmicky Enamel Artist Laura Zell Demonstrating Basic Cloisonné Techniques

- About TAMURA SHIPPO Cloisonne Enamel - TAMURA SHIPPO

goldsteinthreatheen.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cloisonn%C3%A9

0 Response to "Chinese Copper Vase With 6 on the Bottom Copper Shell and Art Work"

Postar um comentário